Neurons are electrically excitable cells that typically interconnect to form complex networks with emergent properties that regulate thought, organ function, and behavior. Although networks of neurons are required to perform these advanced functions, much can be learned by studying neurons as the single cell level, and drugs designed to act on individual neurons can greatly influence function of these advanced networks.

In a simplified view, neurons sense inputs (chemical signals released from upstream neurons) and combine these signals to produce an output (chemical signal release) that may influence downstream neurons. Pharmacological modulation of any of these steps (signal sensing, integration, or signal release) at the level of the individual neuron may profoundly change the way the entire network operates. Discovering how pharmacological agents interact with pathways implicated in a disease can be an important first step toward developing therapeutics aimed at treating it.

Whole-Cell Patch-Clamp Technique

Electrical properties of neurons and networks are often studied using in-vitro brain slice preparations. Thin slices of living brain tissue (typically 300 microns thick) can be sectioned such that many of the neurons inside are unperturbed and the networks they are part of are preserved. Neurons in brain slice preparations can even communicate with each other similar to how they do when they are in a living animal.

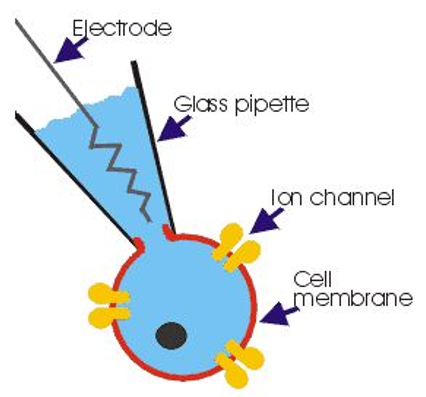

Patch-clamp technique can be used to measure the electrical properties of individual neurons in brain slice preparations. Fine glass pipettes can be pulled to a point about one micron in size with a very small hole at the end. Scientists can fill a pipette with an artificial cytoplasm, lower it into a brain slice, and puncture a single neuron. Since the pipette solution conducts electricity and is continuous with the cytoplasm of the neuron, the electrical properties of the pipette can be measured to infer electrical properties of the cell it is puncturing.

The artificial cytoplasm (called pipette solution or internal solution) contains molecules typically found inside a neuron (K+, Ca2+, Ca2+ buffer, ATP, GTP, etc.). Experiments are performed on brain slices submerged an extracellular solution consisting of oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing molecules typically found in CSF (Cl-, Na+, buffering agents, etc.).

💡 An easy way to remember which ions are inside vs. outside neurons is to recall that neurons evolved in the ocean, so the major ions in salt water (Na+ and Cl-) are in high concentrations outside the neuron. Other ions (largely K+) exist at higher concentrations inside the neuron.

Ion Channels and the Cell Membrane

What is actually being studied when a neuron is recorded? Since patch-clamp recordings measure the electrical difference between intracellular vs. extracellular solutions, what gets measured is just the thing that separates the two: the cell membrane. When we use patch-clamp technique characterize the electrical properties of a neuron, we really reporting the electrical properties of the membrane that forms the cell we are puncturing.

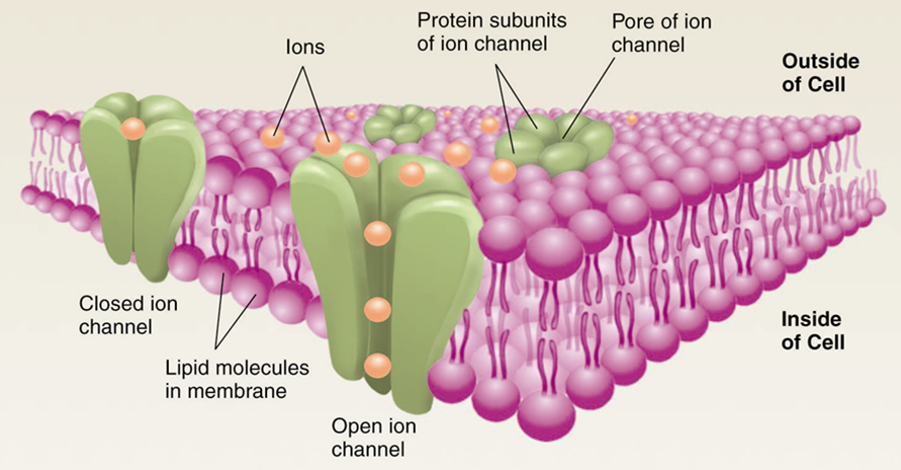

Resistance is the degree to which a material resists the flow of ions. Since cell membranes are largely made of phospholipid bilayers, cell membranes have a high resistance. This means they do not readily permit the passage of ions without the help of membrane-embedded proteins that serve as channels for charged molecules (ions). Neural membranes contain large numbers of ion channels which act like little holes in the membrane and permit the flow of particular ions in or out of the neuron, reducing the membrane resistance while the channels are open. The inverse of resistance is conductance, and opening ion channels in the neural membrane increases conductance (and decreases resistance). There is a wide variety of ion channels, and they typically vary by what ions they pass (influencing whether they are excitatory or inhibitory) and what controls their open state (always open, gated by voltage, and/or gated by ligand binding).

Inward and Outward Currents

The flow of ions is called current, and the total amount of current flowing through all channels in the neural membrane is called membrane current. An excitatory current is one where positive ions rush into the cell (inward current), whereas an inhibitory current is one where positive ions (cations) rush out of the cell (outward current). For example, Na+ rushing into a cell produces an inward current and is excitatory (depolarizing). Outflow of K+ produces an outward current and is inhibitory (hyperpolarizing).

The terms “inward” and “outward” can also be used to describe the flow of negative ions (anions). Gaining a negative ion is roughly equivocal to losing positive ion. For example, Cl- rushing into a cell produces an outward current and is inhibitory (hyperpolarizing). Outflow of Cl- is excitatory and produces an inward (excitatory) current.

It is important to gain conversational use of these terms since electrophysiologists frequently describe currents as inward or outward instead of using the terms excitatory/inhibitory or hyperpolarizing/depolarizing.

What causes an ion to rush in or out of a cell? Is is mostly a combination of the concentration of that ion on each side of the membrane and the voltage across the membrane. This topic is discussed in additional detail on the page about reversal potentials.

Cell Voltage

Voltage is a term that refers to the separation of charge between two points. In a battery, voltage is the separation of charge between the poles (about 1.5 V for a AAA battery). In a neuron, voltage is reported as the separation of charge between the intracellular and extracellular solutions separated by the cell membrane. Neurons typically have a resting voltage near -70 mV.

The voltage of neurons changes when excitatory or inhibitory currents flow across their membrane. A slight excitatory current applied to a neuron resting at -70 mV may raise its voltage to to -65 mV. If a strong enough excitatory current is applied, or many small excitatory currents are simultaneously applied, the accumulated excitation may be great enough to push the cell above its action potential threshold (often near -40 mV) and result in an action potential (AP). Action potentials are discussed in greater detail in the Action Potentials page

💡 Note: The resting voltage of a neuron is typically shown as -70 mV but in practice can be anywhere from -90 mV to -30 mV. The primary reason neurons rest negative is because Na+/K+ pumps embedded in the neural membrane pump a large concentration of K+ into the cell, and perpetually-open potassium leak channels (KLEAK) allow it to flow out. The loss of a positive K+ ions produces an outward (inhibitory) current, driving the cell toward negative resting voltages.

Voltage vs. Current

Why is voltage so often not directly measured by electrophysiologists? You may observe the majority of electrophysiology publications report important findings as changes in current rather than voltage. Voltage is very important to neural function, and it is the primary factor determining if a neuron will fire or not. Although voltage is the important property, membrane currents are what control the voltage of a neuron. To better study how a drug produces subtle shifts in the excitability of a neuron, it is often most desirable to study how that drug changes membrane currents by modulating the conduction of ion channels, rather than study the voltage swing that occurs as its downstream effect.

Common Measurements and Units

-

Resistance is measured in Ohms (Ω). We work with resistances in the megaohm (MΩ) to gigaohm (GΩ) range.

-

Voltage is measured in Volts (V). Neurons operate in the millivolt (mV) range.

-

Current is measured in amperes (A). We work with currents in the picoamp (pA) range.

-

Capacitance is measured in Farads (F). We work with capacitances in the picofarad (pF) range.

🤓 Nerd Alert: Charge is measured in Coulombs (C). Current is the flow of charge, and 1 A = 1 C/sec. When the area under a voltage-clamp curve is measured (Amps × sec), the units are Coulombs (or Femtocoulombs). Note that 1 pA × 1 ms = 1 fC. Conductance (1/R) is often reported in Siemens (S) units. The typical conductance of a single ion channel is in the µS (microSiemens) range.